QUALIS ARTIFEX PEREO

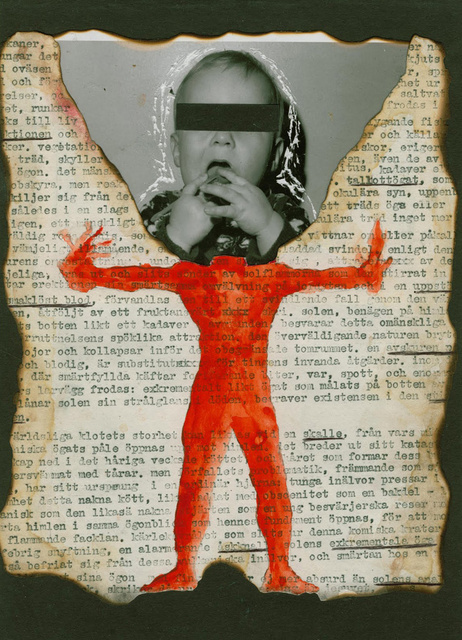

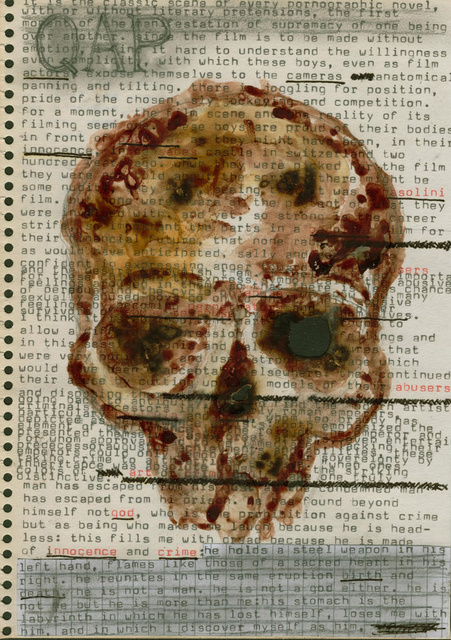

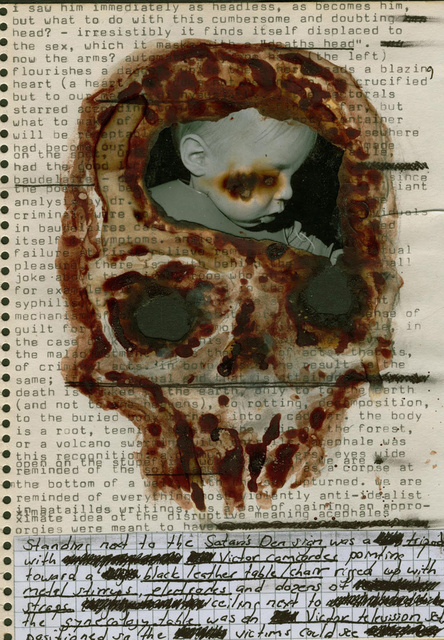

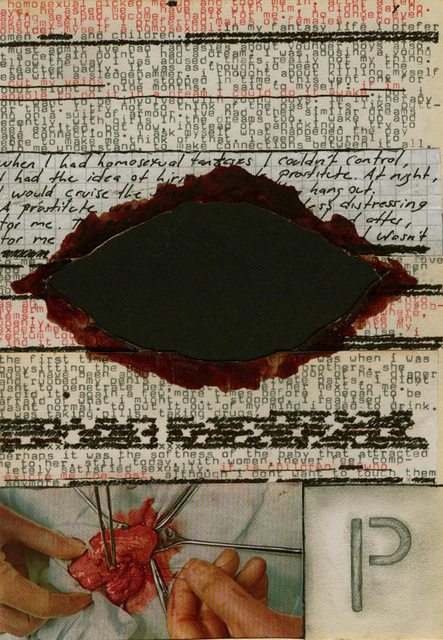

1. Georges Bataille – The Sacred Conspiracy: Man has escaped from his head just as the condemned man has escaped from his prison. He has found beyond himself not God, who is the prohibition against crime, but a being who is unaware of prohibition. Beyond what I am, I meet a being who makes me laugh because he is headless; this fills me with dread because he is made of innocence and of crime; he holds a steel weapon in his left hand, flames like those of a Sacred Heart in his right. He reunites in the same eruption Birth and Death. He is not a man. He is not a god either. He is not me but he is more than me: his stomach is the labyrinth in which he has lost himself, loses me with him, and in which I discover myself as him, in other words, as a monster.

2. André Masson quoted in Critique, 1956: I saw him immediately as headless, as becomes him, but what to do with this cumbersome and doubting head? – Irresistibly it finds itself displaced to the sex, which it masks with a “death’s head.” Now, the arms? Automatically one hand (the left!) flourishes a dagger; while the other kneads a blazing heart (a heart that does not belong to the Crucified, but to our master Dionysus). […] The pectorals starred according to whim. Well, fine so far, but what to make of the stomach? That empty container will be receptacle for the Labyrinth that elsewhere had become our rallying sign. This drawing, made on the spot, under the eyes of Georges Bataille, had the good luck to please him. Absolutely.

3. Patrick Waldberg – Acéphalogramme: The war had burst upon us, Acéphale vacillated, undermined by internal dissensions, its conscience shattered perhaps by its obvious incongruity in the face of world-wide disaster. At the last meeting in the heart of the forest, there were only four of us and Bataille solemnly requested whether one of the three others would assent to being put to death, since this sacrifice would be the foundation of a myth, and ensure the survival of the community. This favour was refused him. Some months later the war was unleashed in earnest, sweeping away what hope remained.

4. Suetonius – The Life of Nero: He so prostituted his own chastity that after defiling almost every part of his body, he at last devised a kind of game, in which, covered with the skin of some wild animal, he was let loose from a cage and attacked the private parts of men and women, who were bound to stakes, and when he had sated his mad lust, was dispatched by his freedman Doryphorus; for he was even married to this man in the same way that he himself had married Sporus, going so far as to imitate the cries and lamentations of a maiden being deflowered. I have heard from some men that it was his unshaken conviction that no man was chaste or pure in any part of his body, but that most of them concealed their vices and cleverly drew a veil over them; and that therefore he pardoned all other faults in those who confessed to him their lewdness.

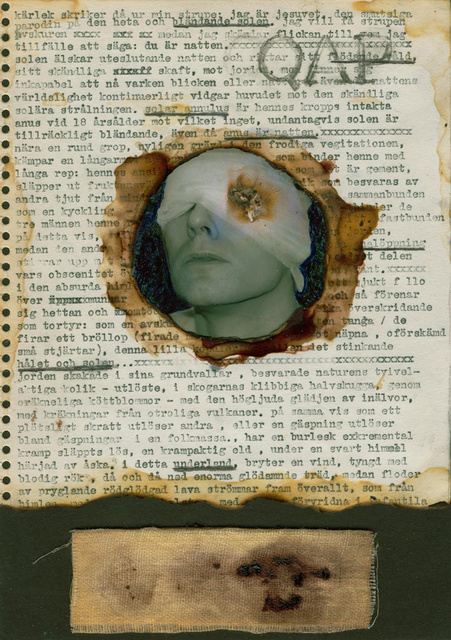

5. Gerard de Nerval – To Alexander Dumas: Was this young Nero, the idol of Rome, the handsome athlete, the dancer, the poet whose only wish was to please the populace? Is this what history and the conceptions of our poets have left of him? Ah, give me his fury to interpret; his power I would fear to accept. Nero! I have comprehended thee, not alas! according to Racine, but according to my own heart, torn with agony whenever I have ventured to impersonate thee! Yes, thou wast a god, thou who wouldst have burned Rome. Thou wast right, perhaps, since Rome had insulted thee!

6. Joel Black – The Aesthetics of Murder: Going back to antiquity, we can find the modern artist-criminal’s ancestors in the early Roman emperors, particularly Caligula and Nero, whom Leo Braudy has depicted as performance artists:”Both emphasized the element of performance in the role of the emperor and presented themselves as great artists, even entertainers, for whom approval had to be immediate.” Lacking their predecessor Augustus’s achievements and abilities, these emperors could only demonstrate their sovereignty by taking crime to a theatrical extreme. “When one’s inheritance was absolute power, only the striking colours of art or crime could make one truly distinctive.

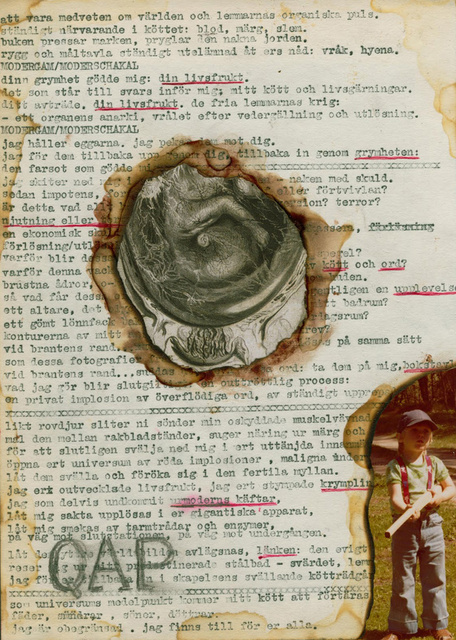

7. Guido Ceronetti – The Silence of the Body: Maybe Gilles de Rais should have been put in an asylum and asked to make collages at the first sign of the cravings for orgies and massacres seething within him. He would have found and outlet for his madness and been cured. His extraordinary collages would have sparked endless discussions. He would have been reborn as an artist who carried the seed of great crimes. But we would never have known that he carried them, just as we do not know how much crime is contained and submerged in the expiating ergon of certain great artists who never cease to amaze.

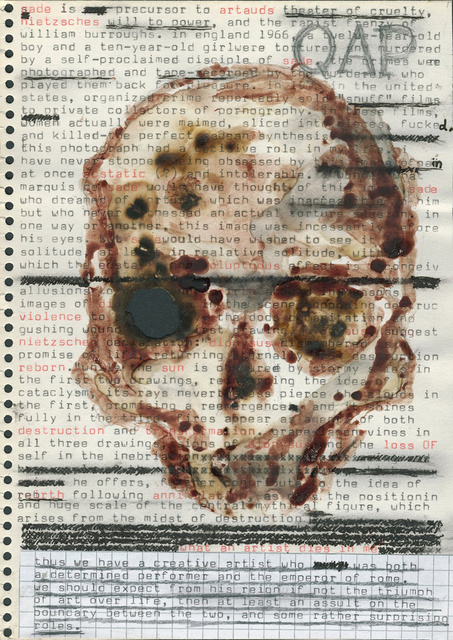

8. Jim Fielder – Slow Death: Standing right next to the Satan’s Den sign was a tall tripod with a very expensive RCA Victor camcorder pointing toward a large black leather table/chair rigged up with metal stirrups, electrodes and dozens of red plastic straps. Hanging from the ceiling next to what looked like the gynaecology table was a RCA Victor television set, positioned so the female victims could see what Ray was doing to them.

9. Gideon Bachmann – Pasolini and the Marquis de Sade: It is the classic scene of every pornographic novel, with or without literary pretensions, the first moment of the manifestation of supremacy of one being over another. Since the film is to be made without emotion, I find it hard to understand the willingness, even complicity, with which these boys, even as film actors, expose themselves to the camera’s anatomical panning and tilting. There is joggling for position, pride of the chosen, sly jockeying and competition. For a moment, the film scene and the reality of its filming seem one. These boys are proud of their bodies in front of Pasolini as they might have been, in their innocence, in de Sade’s castle in Switzerland two hundred years ago. When they were picked for the film, they were not told about the script. There might be some nudity, they knew, seeing that it was a Pasolini film. But none were aware of the portent of what they were involved with. And yet, so strong is the career strife, so important the parts in a Pasolini film for their financial future, that none rebels.